By Sharon Chan, MA

We often focus on noticing and changing unhelpful/dysfunctional thought patterns in therapy, sometimes known as cognitive restructuring. In Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) we may use strategies such as putting on one’s detective hat to check the facts and search for evidence to the contrary, or to think in terms of realistic probabilities. There are many times however, when we are aware that thoughts are unrealistic, improbable, or downright illogical, yet they continue to resurface and cause us distress. At these times, it is helpful to remember that thoughts are merely composed of a bundle of words and images in our mind and they don’t actually exist in the real world. Thoughts themselves do not affect our day to day lives, but rather thoughts lead to emotions, which then bring about urges, which themselves may or may not turn into actions. Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT) builds on CBT by recognizing that sometimes we can’t eliminate our unhelpful thoughts entirely, but we can certainly reduce the power they have over being able to live a value-driven life and make wise decisions at choice points.

In ACT, there is a focus on cognitive defusion, or defusing from our thoughts. When we are fused with a cognition – a thought, belief, emotion, or memory – it becomes overwhelming and interfering with goals. When you are fused with a cognition, it may feel like you have to obey, give in, or act upon that thought. In ACT terms, you get hooked by cognition. The thought may feel like a threat that you need to avoid, get rid of, or give into. Thoughts may seem very important, a loud demanding presence that commands your attention.

When we defuse from our thoughts, we lessen the urge to obey, given into, or act upon the thought, and no longer see it as big of a threat. It may or may not be important – we have a choice as to how much attention we pay to it.

Now you may be wondering, why can’t we just get rid of or change the thought? Sometimes (E.g., in CBT) we can do this and it is helpful to do so. I invite you to try a few thought experiments right now to illustrate why this doesn’t always work. I want you to think of the last time you left the house in detail. Where did you go? What were you doing? What were you wearing? How did you get there? What happened along the way? Remember this outing in as much vivid detail as you can remember. Do you have it? Okay great, now I want you to just forget about it. Erase this memory completely from your mind, go on, just delete it. It was a boring, unremarkable memory anyway. You can’t, can you? At least not on command.

Now, I want you to imagine this next scenario: I have presented you with a prospective romantic partner, one who is incredibly misogynistic, bigoted, unkind to children and animals, has questionable hygiene, is astonishingly rude, and physically unattractive to boot. Conjure this person up in our mind. Have them? Good. Now, what if I told you I would give you a billion dollars if you could just fall in love with them. No, I don’t mean to put on a pretense of love with grand gestures and a golden-globe worthy display of affection between your internal cringing and despair, I mean actually fall in love with this person. Can you do it? No?

Try this next one. Imagine that I was a mad scientist and had you hooked up to a special machine and told you, as soon as you feel anxious, a painful current of electricity would zap you. The more anxious you are, the stronger the zap, and there is no limit on how powerful the zaps can get – you could literally die from being zapped. Can you stop feeling anxious? Come now, your life is at stake. Can you stop feeling anxious? Not even to save your life?

What these thought experiments illustrate is that we have less control over our thoughts and emotions than we’d like, and the sooner we give up the illusion that we can control them, eliminate them, change them, the sooner we can turn our attention to making goal and value driven choices despite them. Like uninvited guests, thoughts and emotions will always find a way of traipsing into our consciousness, and sometimes they are even there for good reason to tell us important information. What we want to do is to defuse from our thoughts rather than eliminate them. To lessen their power over us.

The father of ACT, Russ Harris, would say there are several broad categories of cognitive fusion:If you are fused with the past, you may find yourself constantly ruminating and feeling regretful. You may dwell on painful memories of failure, loss, rejection. You may feel resentment over past events and feel blame-oriented. You may experience flashbacks and idealize the distant past before XYZ happened. You may convince yourself that you can’t do [insert important action] because of the way [insert bad past event] affected you and your life.

If you are fused with the future, you may find yourself constantly worrying, catastrophizing, predicting the worst, and feeling hopeless. You may anticipate failure, rejection, hurt, and idealize a distant future when all your problems are solved (“My life will be perfect when XYZ happens). Assuming a bad outcome may lead to inaction. For example, I can’t do [insert important action] because [bad outcome] will happen.

Fusion with self may take the form of overly negative or overly positive self-judgments, or over identifying with certain roles (being a “parent”, being “sick”, being in a certain occupation) or over-identifying with a label (e.g., “I am borderline”). Sometimes, what might be most painful is not knowing who you are at all.

Others may find themselves cognitively fused with reasons, for example, all the reasons why I can’t or won’t change. I can’t do X because…, I’m too…, I’ve tried before but…, I shouldn’t have to, it’s their fault…I can’t because it’s pointless, too hard, too scary, impossible…

One might also be overly fused with “rules” about how others, one’s self, or the world should be. Fusion with rules can be identified by using words like should, have to, must, ought, right, wrong, fair, unfair.

We might also be fused with judgments, which may include negative or positive judgments about the past future, self, others, thoughts and feelings, life, body, the world.

If you find yourself cognitively fused with one or more of these categories, and many of them are interrelated, it may be helpful to spend some time on practicing some cognitive defusion techniques.

One technique that can be used to practice cognitive defusion is the ‘Naming the Story’ technique. Here’s how it works:

Find a phrase that non-judgmentally describes the unhelpful mental process you engage in, the thought that ‘hooks’ you onto the unhelpful path. Take that unhelpful thought, feeling, or memory that you replay over and over in your mind and imagine it is a video that your brain stores in its video archive. What would this story be called? Give it a catch-all title that summarizes the narrative. Maybe it’s the “Jane Doe is a failure” story, or the “Unlovable John Doe” story. Whenever you’re feeling hooked in by those emotions that overwhelm and dominate you, you tell yourself, “Aha! Here it is again, the _________story. My mind wants me to watch that movie again. You might say, “Okay, brain *sigh* let’s watch that story again if you really insist,” much as you would address a petulant child who is pulling you towards a store that you don’t want really want to visit but will indulge them in visiting anyways. Once we become aware of this thought happening, we recognize it’s just that – a film that your brain has decided to put on in that moment. Observe the distance that is created between yourself and this thought, notice how it becomes less of a threat. As this distance increases, as the thought becomes less compelling, decide what decisions, actions, and steps you can take to realize your goals in life. Are they behavioural goals? What do you want to do in life? Emotional goals? How do you want to feel? Or maybe outcome goals? What do you want to get or have?

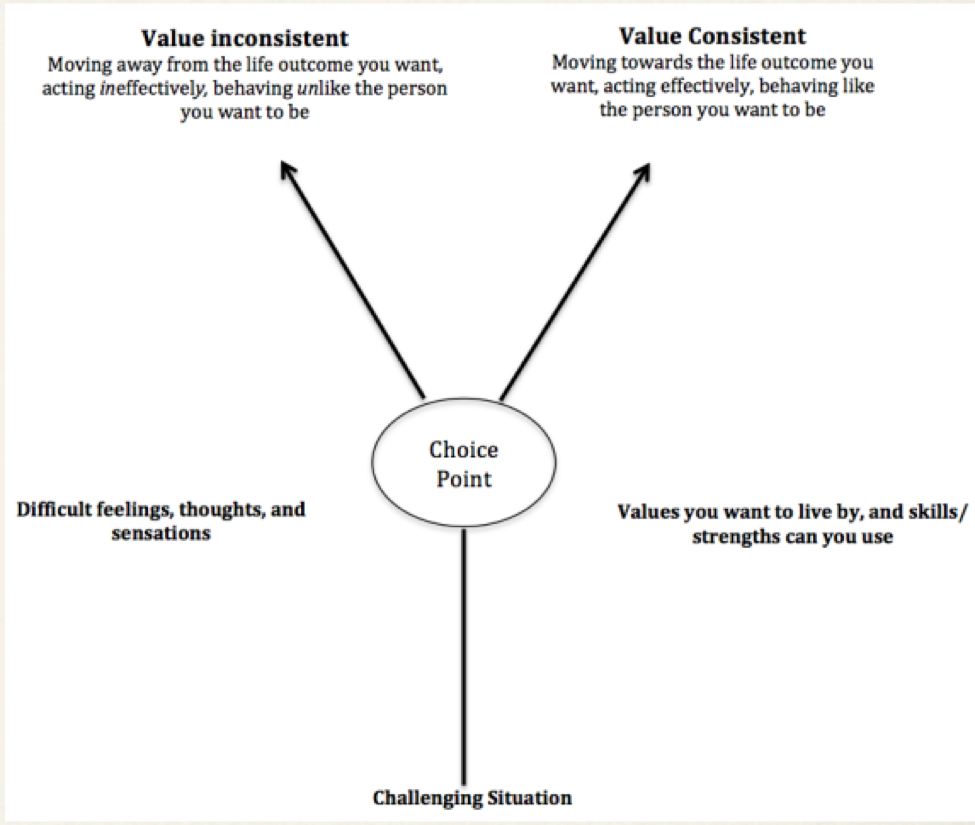

Defusion techniques help us to instill a sense of separation or distance from our cognitions. We notice the thought or emotion, name it, then neutralize it. You decide mindfully if you want to act on it, or let it dictate your choices and take away from the life you want to live. ACT describes these junctures as ‘choice points’ (see figure below):

When we encounter a challenging situation, various unhelpful cognitions – thoughts, emotions, memories, beliefs – may “hook” us into unhelpful actions that actually move away from the goals and values we deem important towards a meaningful life. Becoming aware of being ‘hooked’ in the moment allows us to mindfully take the other path, to act, respond, and make decisions that are consistent with your values, goals, and the type of person we want to be.

DeAlmeida, D. (2019). Photograph. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/ODNe1jriB4Y

Fakurian Design. (2021). Photograph. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/58Z17lnVS4U

Harris, R. (2019). ACT made simple: An easy-to-read primer on acceptance and commitment therapy. New Harbinger Publications.

The Humantra. (2020). Photograph. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/68n3VbbLDgA

Tucious, K. (2020). Photograph. Unsplash. https://unsplash.com/photos/7qT9A9QzcUA